Unwinding the Mystery of the Gyroball (Part III)

The Gyroball > Part I > Part II > Part III > Part IV

As speculation grew over the past season about whether Matsuzaka would indeed make the jump to the big leagues, the story of the gyroball slowly slipped its way across the Pacific and into baseball circles as yet another Japanese wonder, like the 15,000-yen melon or the love hotel. Each Matsuzaka gem conjured up yet more Godzilla-like mythic creature imagery than the one before.

Perhaps some gyroball hype is justified; in baseball's century and a half in existence few pitches have simply emerged.

Perhaps some gyroball hype is justified; in baseball's century and a half in existence few pitches have simply emerged.

Following arm surgery in the early '70s, right-hander Bruce Sutter abandoned his fastball and relied on the drop of the split-fingered fastball (a faster version of a forkball) to become one of baseball's greatest closers with the St. Louis Cardinals. The pitch, which to that point had not been widely used, eventually landed him in the Hall of Fame.

Fernando Valenzuela did not invent the screwball but he did drag it off the scrap heap in 1981, the year the chubby left-hander won the National League Rookie of the Year and Cy Young awards for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Matsuzaka is different. He doesn't need a gadget pitch; he dominates with his entire repertoire, with many experts saying that his change-up is his most devastating pitch.

As an 18-year-old in 1999, he won 16 games and took the Pacific League's Rookie of the Year crown. In his career, he has piled up 108 wins against 60 losses while boasting an ERA of 2.95.

Back at the theater at Riken, Himeno has grabbed a plastic bat that has had two sensors attached at both ends of its hitting zone. A small device in the floor that emits a magnetic field is acting as home plate. Both pieces of equipment are hooked up to Himeno's computer.

Boston manager Terry Francona, who has studied Matsuzaka on video, is quoted as postulating the gyroball to be a screwball (the opposite of a curveball) that acts as a change-up.

Boston manager Terry Francona, who has studied Matsuzaka on video, is quoted as postulating the gyroball to be a screwball (the opposite of a curveball) that acts as a change-up.

After hearing of such a comparison, Himeno shakes his head. "The gyroball," he says, "is much faster than a change-up." He approximates that Matsuzaka's two-seam gyroball reaches the plate at around 140 kph.

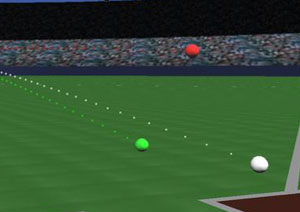

Himeno taps a few keys and a computer rendition of a baseball stadium (from the hitter's perspective) appears in place of the rotating baseball from before. A cartoon pitcher stands on the mound. He winds and a pitch tumbles out of his hand.

Himeno, who describes himself as a scientist with only a passing interest in baseball, takes his best hack. There is contact.

"You can see the drop," Himeno says, letting the Whiffle bat fall to his side. "The model shows the gyroball at the same speed, same direction, and same timing as a pitch would behave in the field."

The computer then dishes out three pitches simultaneously: a fastball, a forkball, and a gyroball. Dashed lines of different colors stream from behind the advancing balls to represent the different trajectories.

The model shows the gyroball to nearly follow the path of the forkball. The fastball's line is left suspended far above the other two.

"Tezuka claims that sometimes the gyroball has 'hops,'" Himeno says, shrugging his shoulders.

"Tezuka claims that sometimes the gyroball has 'hops,'" Himeno says, shrugging his shoulders.

Tezuka's tiny, cramped office is on the fourth floor of the Beta Endorphin building. DVDs and VHS tapes fill the shelf in front of his desk. Next to his chair is a computer monitor.

The birth of the gyroball can be traced back to 1995. Tezuka was observing some students playing catch. One of them was throwing particularly hard. After watching the delivery of his pitches, Tezuka knew something special was taking place.

"It was then," remembers Tezuka, "that I discovered the gyroball. I knew that this was no ordinary pitch."

The benefit of the four-seam gyroball, Tezuka says, is its surprising explosiveness. Batters, he believes, are lulled into thinking a typical fastball is approaching only to find it already streaking through the zone as they start their cut. But most gyroballers, he says, throw the two-seam version because of its extreme movement.

"The gyroball is scary," says Tezuka, of the pitch's speed and unpredictability. "It is beyond imagination."

On his computer he brings up videos of high school players throwing gyroball training balls. The slow-motion footage, which was shot with a camera set directly behind home plate, shows the plus mark (+) on the ball to be generally visible and slightly weaving as it approaches home.

Tezuka then switches to highlights of Shunsuke Watanabe, a starting pitcher for the Chiba Lotte Marines, one of four pitchers in Japanese professional baseball who has pitched the gyroball in the last few years, according to Tezuka.

In his 5,000-yen instruction DVD Jairoboru no Nagekata (The Way to Pitch the Gyroball), Tezuka emphasizes the importance of lowering the throwing shoulder.

In his 5,000-yen instruction DVD Jairoboru no Nagekata (The Way to Pitch the Gyroball), Tezuka emphasizes the importance of lowering the throwing shoulder.

Watanabe is a sidewinding, two-seam gyroballer. He drops down with his arm so far that he almost scrapes the dirt on top of the mound. His gyroball then is delivered with his fingers roughly parallel to the ground.

Batter after batter can be seen flailing at Watanabe's high hard stuff. None of his pitches, however, are seen dropping like a forkball, as predicted by Himeno.

When asked about the difference between his computer results and Tezuka's observations in the field, Himeno didn't have a clear answer. He supposed though that in a practical sense pitchers are more apt to throw the gyroball variation where the lift force causes the pitch to drop less.

Tezuka's theory, however, is that if a pitcher releases the ball from as low as possible it will not sink as it crosses the plate.

Professor Adair is doubtful, alluding to the effect as an illusion. "A pitch cannot rise as it crosses the plate," he says. "Gravity impacts the trajectory upon its release from the hand. The distance is too far for the ball to rise."

Adair concedes, however, that it might be easier for a pitcher to release a gyroball from a sidearm position. "Certainly," the professor says, "it gives a different angle to the batter. It will disrupt the way that he typically recognizes a pitch."

Tezuka changes the monitor to show highlights of Sandy Alomar Jr. and Barry Bonds facing the now retired Tetsuro Kawajiri of the Hanshin Tigers, another two-seam gyroball pitcher (or so says Tezuka). The footage is from the 2000 MLB All-Star tour of Japan.

The sidearmer fires multiple pitches into the strike zone. Alomar is seen to ground out weakly to shortstop. Bonds pops out to center. Each hitter's swing seems to have been slightly off balance.

The sidearmer fires multiple pitches into the strike zone. Alomar is seen to ground out weakly to shortstop. Bonds pops out to center. Each hitter's swing seems to have been slightly off balance.

Tezuka grabs a paper cup, gripping it around the rim and pointing it in front of himself. He then quickly shifts it up, down, and side to side as if to mimic a moving ball.

"For both the hitter and the catcher," he says of the two-seamer, "they don't know what's going to happen."

In The Truth about the Supernatural Pitch, close-up frame captures of a television broadcast showing Kawajiri's release are reproduced. Given the low quality of the images, however, it is not clear how the rotation achieved is different from a regular two-seam fastball.

All four of the gyroball specialists Tezuka named - with Tomohiro Umetsu of the Hiroshima Carp and Tomoki Hoshino of the Seibu Lions being the others - are sidearmers.

In fact, Tezuka says that a gyroball can only be pitched sidearm style - it is impossible to throw any other way. So where then does that place the most famous gyroballer of them all, the young phenom who throws overhand?

A gyroball, Tezuka calmly explains, is not what Matsuzaka throws. "He throws a sinking slider."

The Gyroball > Part I > Part II > Part III > Part IV