In with the Old: Yokohama's Red Brick Warehouses

"Where the hell is the Yokohama red brick warehouse story!┼hscreamed junior reporter Junko, running into my office; fire in her eyes, papers gripped in her right fist.

Oftentimes the newsroom can resemble a battlefield. I find it amusing to see reporters dueling in the trenches while mortar hurtles down from overhead, myself playing the part of field general, calling out maneuvers and formations from my office chair.

Oftentimes the newsroom can resemble a battlefield. I find it amusing to see reporters dueling in the trenches while mortar hurtles down from overhead, myself playing the part of field general, calling out maneuvers and formations from my office chair.

Oh sure, I was once in their boots and fatigues. But I've since paid my dues, and come to realize that the difference between victory and defeat is often decided by a newsman's ability to arrive at the office prepared; faculties in top form, always being the sharpest tack in the box.

Take today: one yak buys the farm and another suffers serious leg wounds in a coffee shop shootout in Kabukicho. Field reporters at the scene fax in copy. Editors in the newsroom pull it off the machine, puff on a few cigarettes, and then bark: "Throw it on the wire!" Mere minutes separate the planting of the flag of victory from a lined coffin with brass handles.

The knives-drawn combat nature of this business is something the wet-behind-the-ears reporter has to get used to. But for the hardened newsman, like myself, his polished skills and sage-like experience are usually better utilized in compiling thought-provoking features. Through skillful wit and tight prose, he will provide insight into a people, or perhaps an event, that is shaping our community, maybe even our world.

The knives-drawn combat nature of this business is something the wet-behind-the-ears reporter has to get used to. But for the hardened newsman, like myself, his polished skills and sage-like experience are usually better utilized in compiling thought-provoking features. Through skillful wit and tight prose, he will provide insight into a people, or perhaps an event, that is shaping our community, maybe even our world.

With this understanding of roles, I can overlook the occasional lack of respect from the hothead in high heels. Quietly sending her on her way with whatever she has requested is the best way, I've learned, and I might even smile.

Kuniko Kitamura waves her hand and points at the open plaza in between the two brick buildings. The morning rain has stopped and the area is filled with young couples out shopping. "It is very nice to preserve the old buildings of Yokohama, "she says. "It makes for a different atmosphere."

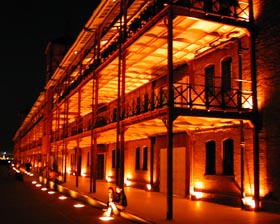

The two brick buildings are former shipping warehouses from the early part of the last century that have been renovated to today house fancy shops, restaurants, and art exhibition rooms. More important though, the project represents a breath of fresh air that blows through Japan very infrequently: a preservation of the past in the face of a seemingly never-ending onslaught of new shopping centers and housing complexes.

It has never been a tradition for Japan to preserve her cultural landmarks. Historic buildings utilizing architectural styles from Japan's past are often demolished quickly with no, or very little, protest. This was especially true during the booming economy of the '70s. Many areas rich in cultural heritage, such as Kyoto and Nara, suffered great losses. Even today, older houses in Tokyo are being demolished at an alarming rate to make way for multi-story apartment complexes. As a result, this preservation project at the edge of Yokohama's Harbor is a step in a different direction.

It has never been a tradition for Japan to preserve her cultural landmarks. Historic buildings utilizing architectural styles from Japan's past are often demolished quickly with no, or very little, protest. This was especially true during the booming economy of the '70s. Many areas rich in cultural heritage, such as Kyoto and Nara, suffered great losses. Even today, older houses in Tokyo are being demolished at an alarming rate to make way for multi-story apartment complexes. As a result, this preservation project at the edge of Yokohama's Harbor is a step in a different direction.

Construction with red brick in itself is a bit unique as well; few structures in Japan have been constructed at all. But Tokyo Station and the former Hokkaido government office building in Sapporo are perhaps two of the most notable examples.

Similar to the transformation that took place in Yokohama - a former place of industry becoming a place of public gathering, a sister project was completed recently in Sapporo with the former Sapporo Beer factory. With its towering smokestack and red brick walls still preserved, the former brewery has been modified into a home for clothing stores, restaurants, a beer hall, and a movie theater, all beneath Japan's largest glass-roofed atrium.

In keeping with the methods of the factory restoration, the exteriors of Yokohama's warehouses (referred to as Warehouse No. 1 and No. 2) have been held largely to that of the original. It is the insides that have been given a modern touch.

In keeping with the methods of the factory restoration, the exteriors of Yokohama's warehouses (referred to as Warehouse No. 1 and No. 2) have been held largely to that of the original. It is the insides that have been given a modern touch.

During the eight-year project that was officially finished in the spring of this year, the brick archways above the windows and the iron sheeting and corresponding fastening rivets have been kept in place and painted. Additionally, large iron interior sliding doors and their fixtures and roof trusses have been restored to that of their industrial glory. The safety of both structures was ensured through structural improvements and roof renovations. Faux brick paneling has been added to many interior walls to give an authentic feel.

Inside Warehouse No. 1, amid its galleries and photo exhibitions, selected sections of its three floors and stairways have been constructed of heavy see-through plastic to reveal some of its original building materials and artifacts: a cut section of a steel beam imported from England, a few of the original metal roof lightning rods, and even some single bricks. Warehouse No. 2 is dedicated to antique stores, knick-knack shops, a beer restaurant, and Motion Blue Yokohama - a live venue associated with Blue Note Tokyo.

When he first put pen to sketch pad in 1908, architect Yorinaka Tsumaki likely had no idea what sort of attention his creations, each originally of 3 million bricks each, would muster nearly a century later. Warehouse No. 2, the larger of the pair, was completed in 1911. Its twin sister was finished two years later, though the Great Kanto Earthquake twelve years later would cut its length in half to roughly 75 meters. After serving as a key hub in Japan's export trade until 1989, the buildings have since been the subject of plans to exhibit the culture and history of Yokohama's port.

When he first put pen to sketch pad in 1908, architect Yorinaka Tsumaki likely had no idea what sort of attention his creations, each originally of 3 million bricks each, would muster nearly a century later. Warehouse No. 2, the larger of the pair, was completed in 1911. Its twin sister was finished two years later, though the Great Kanto Earthquake twelve years later would cut its length in half to roughly 75 meters. After serving as a key hub in Japan's export trade until 1989, the buildings have since been the subject of plans to exhibit the culture and history of Yokohama's port.

Though Kitamura, a single retiree in her early '60s, finds the restoration overall to be quite nice, there are many distinctly Japanese features that this Yokohama resident could do without; a number of entranceways are graced with automatic glass doors; and elevators, escalators, and stairways connecting the various floors within the structures are made of glass and steel, many exposing their shining moving parts beneath. These modern additions contrast with the organic feeling of the original brick, she says.

Still, she would like to make it clear that the project, surrounded by a small park at the harbor's edge, is a good sign. Likewise, so is the fight to prevent the construction of a series of large condominiums in the nearby Yamate residential neighborhood, a neighborhood whose origins go back nearly 150 years.

Still, she would like to make it clear that the project, surrounded by a small park at the harbor's edge, is a good sign. Likewise, so is the fight to prevent the construction of a series of large condominiums in the nearby Yamate residential neighborhood, a neighborhood whose origins go back nearly 150 years.

But it will be some time before Japan's destroy-and-rebuild mentality changes. Around Sakuragicho Station, a 15-minute walk from the warehouses, a massive redevelopment, comprised of stores, restaurants, hotels, office buildings, and amusement centers, has taken place over the past few years. And today, enormous apartment complexes, all nearing completion, loom just beyond.

"I don't like what is happening. I prefer a balance with the past," Kitamura sighs. "In the normal Japanese way, we try to build on every open space."

Note: Kazuko Maruyama contributed to this report from the Yokohama Bureau.