Yubari: Japan's Melon Kingdom

The Quirky Series > Penis Fest > Love Janitor > Maid Cafe > Race Queen > Cosplay > Pastors > Melons > Xmas

Over the course of a year there are three main vacation periods in Japan (all centered around major national holidays), with spring, summer and winter getting roughly one weeklong break a piece. For many Japanese, always dutifully manning their jobs, these are their only opportunities to take a break from the rigors of the working world.

The Captain, equally dedicated to his work, likes to get away from life in the city as well. But instead of returning to his ancestral home, this week he braves the throngs and travels to the inner regions of Japan's north island of Hokkaido during spring's Golden Week. There, he discovers a town whose hopes rest on its melon industry. Why not tag along with him? He won't help you with your bags, but he might extend his cigarette pack.

The Captain, equally dedicated to his work, likes to get away from life in the city as well. But instead of returning to his ancestral home, this week he braves the throngs and travels to the inner regions of Japan's north island of Hokkaido during spring's Golden Week. There, he discovers a town whose hopes rest on its melon industry. Why not tag along with him? He won't help you with your bags, but he might extend his cigarette pack.

It is midmorning at the rest area outside the entrance gate of Yubari's coal mining amusement park. The dining hall is long and wide, with enough seating to accommodate a few busloads of tourists. Staff behind the counter wait patiently to serve Japanese noodle dishes, curry, and drinks to folks arriving to perhaps enjoy such attractions as the coal miner's lifestyle exhibition hall, the coal museum, or one of the two roller coasters.

While a theme park dedicated to the coal mining industry might not inspire visions of grandeur to the average Japanese like, say, Tokyo Disneyland, Yubari has few other choices. Tourism is one of its main industries now that its mines have closed. In addition to the amusement park, beautifully painted movie poster boards of years gone by hang from the sides of many buildings in the center of town. This is coupled with the annual "Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival," a festival that this year featured films from South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. There is also a ski resort.

"We have a lot of customers when the tour buses come," says one female worker, seated next to the grill. Today, however, there are none. The 2,500-car capacity parking lot is nearly empty.

The steady rain on this day might be a reason for the lack of visitors. But a quick tour of this town, located about one and a half hours by train from Sapporo, reveals a place and a people struggling to cope with a little more than some rain showers. The death of the mines is taking its toll: a large grocery store closes at three in the afternoon; a man working at a printing shop rushes to his window at the sounds of passersby, likely the only ones of the day; pockmarked along the town's main road, many homes and shops have plywood boards nailed over doors and windows; and, the restaurants - the ones still in business - sit mostly empty at lunchtime.

But this quaint Hokkaido mountain town is still a highly influential force in Japan. For the last few decades, Yubari's revered and highly expensive melons have put smiles on the faces of many Japanese during the summer gift-giving season.

But this quaint Hokkaido mountain town is still a highly influential force in Japan. For the last few decades, Yubari's revered and highly expensive melons have put smiles on the faces of many Japanese during the summer gift-giving season.

The "Yubari King," the brand name as it is known across Japan, today accounts for 97% of Yubari's agricultural income. "This is our main industry now that the mines have closed," explains Katsuhide Totsuka, a 45-year old manager of the Yubari Agricultural Cooperative Association. As a result, much of Yubari's future prosperity rests on the perfected growing process and national reputation of this round and gold gem.

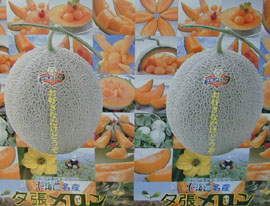

The orange-fleshed Yubari melon, similar in appearance and size to the common cantaloupe, has become a Japanese favorite for giving as a gift of thanks to friends or bosses. In the food section of large department stores, Yubari melons - reputed to be Japan's Cadillac of melons - are often sold for upwards of 15,000 yen (a generic melon might fetch 500 yen). Special apples and strawberries can likewise be sold for exorbitant sums, but as far as luxury fruit goes, nothing tops a nice melon for prestige. Shape, skin netting pattern, sweetness, and texture are key factors in the price. A top-grade perfectly round Yubari number with a smooth skin could command over 20,000 yen.

The presentation of the melons in stores is always immaculate, nearly shrine-like. The melon sits on a pedestal with tissue paper carefully bunched beneath it. A small portion of the stem always remains protruding from the top, perfectly trimmed so that it achieves a symmetrical T-shape. The label of the melon grower is affixed somewhere near its center so that the buyer can easily see if the brand is Yubari or any of the over 50 others produced in Japan. Sometimes a wood box sits nearby to conveniently allow for packaging up that gift for someone special.

The melons first appear on store shelves in May of each year. Usually a Sapporo department store purchases the first melons at a highly publicized open auction. This year Mitsukoshi bought the first two for 150,000 yen each. After the auction, the melons are showcased and put up for bid to the store's customers. Since the first born of the year are said to represent good luck, shoppers can gawk and hope for a little melon fortune to rub off onto them as they peruse the aisles. A few days later, the highest bidding customer can take them home and enjoy them with their morning cereal.

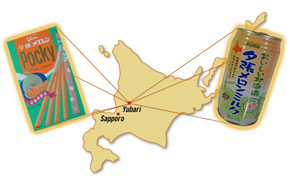

The melon business doesn't stop with just mere sales of the fruit itself. An entire cottage industry dedicated to melon-related products has also been created. In Yubari (and every tourist shop in Hokkaido), melon goods, all with the orange flesh tint and the Yubari Chinese kanji characters prominently shown on the packaging, are readily available: brandy, crackers, cakes, canned drinks, gum, caramel, pudding, and even Pocky. Yubari's Melon Dome, a cylindrically-shaped souvenir stand with a large green orb (presumably a melon) on its roof, dedicates itself to the sales of these products.

The melon business doesn't stop with just mere sales of the fruit itself. An entire cottage industry dedicated to melon-related products has also been created. In Yubari (and every tourist shop in Hokkaido), melon goods, all with the orange flesh tint and the Yubari Chinese kanji characters prominently shown on the packaging, are readily available: brandy, crackers, cakes, canned drinks, gum, caramel, pudding, and even Pocky. Yubari's Melon Dome, a cylindrically-shaped souvenir stand with a large green orb (presumably a melon) on its roof, dedicates itself to the sales of these products.

Still, mention of store prices, auction bids, and associated melon products don't tell the full story of just how valuable these little jewels are in Japan. But the following might: In February of 2000, three people were arrested on suspicion of selling melons bearing counterfeit labels of the Yubari brand. The suspects allegedly bought regular orange-fleshed melons, attached the counterfeit labels, and then resold them for a price that a Yubari would typically go for.

Like Rolex, Gucci, or any other brand worthy of being counterfeited, the Yubari melon's production process is a finely crafted procedure that has been refined over time.

The growing cycle begins in early February with the snow being cleared and the first seeding begins. After 105 days, the first melons are picked. The harvest continues until September, with the peak occurring between June and the beginning of August.

The farms, easily distinguishable by the vinyl greenhouses that are laid out in rows, fan out into the hills of Yubari. Each greenhouse is slightly longer and wider than two lanes of a bowling alley. The seeds are planted in furrows within the houses. The vinyl tenting ensures that Hokkaido's harsh elements are held at bay.

The first melons to originate from Yubari were not the same as what is produced today. In the 1920s, the rugby ball-shaped "Spicy Cantaloupe," based on cantaloupes from the United States, was the main melon farmed in Yubari. This melon was very sweet, had a nice smell, and contained salmon pink flesh. But it lacked a pleasing shape.

Melon production ceased during World War II. In the years following, various attempts were made to develop a solid agricultural industry in Yubari. Potatoes and asparagus were tried - much of which was used to feed coal miners. But extensive research revealed that Yubari's native soil is best if used for growing melons.

Melon production ceased during World War II. In the years following, various attempts were made to develop a solid agricultural industry in Yubari. Potatoes and asparagus were tried - much of which was used to feed coal miners. But extensive research revealed that Yubari's native soil is best if used for growing melons.

Still, Yubari farmers knew that the oblong shape of the "Spicy Cantaloupe" simply would not do. Thus, in 1961, this melon was crossbred with one from Europe known for its nice round shape and exquisite netting pattern. The result is today's "Yubari King." Efforts have been made to use melons sourced from the Japanese mainland, but the resulting melons were always far too fibrous.

Sweetness, says Totsuka, is the "King's" main selling point over its main upper echelon melon rival - the musk melon. This is where Yubari's soil comes in.

Over the years, Yubari's soil has gone through a battery of scientific tests and studies to determine what the ideal conditions are for melon growing. Within each greenhouse, warm water is run through plastic pipes buried just below the soil's surface. Yubari's native soil is rich with volcanic ash, a characteristic that easily allows for the soil temperature to be raised to the optimum level with the water pipe network. Additionally, water can permeate the dark volcanic soil very quickly, allowing for the soil to remain dry - generally an important condition in determining the melon's size. These combined characteristics make Yubari's environment unmatched in Hokkaido and, as Totsuka says, "perfect for growing sweet melons."

But balance is the key. A soil temperature or water content that does not match the time-tested optimum values may result in a melon of undesirable sweetness or size. Other melon growers in Hokkaido have tried to copy Yubari's process, but, as Totsuka maintains, "They can't match our soil."

Falling consumer prices in Japan during the past few years have taken their toll on a variety of economic sectors, from real estate to alcohol - but so far its high-priced melon market has been untouched. Yubari's 280 hectares of land dedicated to melons have produced a very steady 3 billion yen in sales on average over the past three years.

Falling consumer prices in Japan during the past few years have taken their toll on a variety of economic sectors, from real estate to alcohol - but so far its high-priced melon market has been untouched. Yubari's 280 hectares of land dedicated to melons have produced a very steady 3 billion yen in sales on average over the past three years.

The melon business has softened the blow in Yubari's transition from coal dependency over the years. Even with this it hasn't been easy. Yubari's population has been cut in half to just over 14,000 since 1985. This is down from its peak of over 100,000 in the coal boom days in the early part of the last century.

Japan's coal industry had been protected for over 40 years by a practice that made utility companies purchase domestic coal at a rate three times more expensive than imported coal. Yubari's last mine closed just over ten years ago. Today, coal is purchased from abroad, leaving cities like Yubari searching for other means of survival.

Even though Yubari is presently steering itself away from its mining past, the sales procedure for its melons shares a little in common with the old controlled market of the coal days.

The Yubari Agricultural Cooperative Association, an association to which all melon farmers belong, operates a melon trading house in Yubari. It is its own closed market. All Yubari melons are distributed from the trading house to only customers that have placed orders. This way the melon market is never flooded with large quantities of melons, a condition that would cause a fall in price.

"The farmers cannot sell the melons directly to the customers like peach or strawberry farmers," Totsuka explains. "This way the price is controlled and only high quality melons are delivered."

After maturing on the vine, each Yubari melon is carefully hand harvested with scissors and trucked to the trading house. After being washed and weighed, the melons are then run through a strict quality check where they receive one of four grades based on sugar content with the appropriate grade being stamped on their box. Melons that are not sweet enough, and even those that are too sweet, are rejected.

The sales process can be rather hectic in that the prime consumption time is usually within 2 to 3 days of harvesting. At this point, the flesh is turning from green to orange. With this window of freshness being very short, the melons are usually delivered by air to the customers.

The sales process can be rather hectic in that the prime consumption time is usually within 2 to 3 days of harvesting. At this point, the flesh is turning from green to orange. With this window of freshness being very short, the melons are usually delivered by air to the customers.

A trained eye can judge whether a melon is ripe just through a quick visual inspection. A stem that is green and strong is one prime indicator. So is a flexible bottom. This seems easy enough, even for a layman. But some checks can only be performed after years of experience in the melon business; for example, after picking up the melon, it should feel heavier than it looks.

The cooperative association has come a long way since its initial membership of 17 farmers in 1960. At its founding, the farmers knew that growing such a special product necessitated the need for an organization that could promote the positive image of the Yubari melon beyond Hokkaido and assist in research and development. Today, nearly 200 farmers work towards these very same goals set by the founders.

Even with this past success, Totsuka admits that not every aspect of the business is filled with sweetness for the farmers. "Once the last melons are delivered to the customers in early September, there is nothing for them to do during the cold Hokkaido winter until the following January."

Nothing that a little melon brandy hasn't remedied over the years, of that there is no doubt.

The Quirky Series > Penis Fest > Love Janitor > Maid Cafe > Race Queen > Cosplay > Pastors > Melons > Xmas