Factory Tour: Kikkoman Soy Sauce

One recent afternoon junior reporter Junko entered my office from the Newsroom to find me slouched over my desk after what she thought had been a single trip to the Snow Brand Milk Products factory in Chiba Prefecture.

"You look terrible," she said, cupping my chin with hand. "Are you sure you didn't go out boozing after going to the milk factory?"

"You look terrible," she said, cupping my chin with hand. "Are you sure you didn't go out boozing after going to the milk factory?"

At the time, I was having a little trouble convincing her that I later visited the Kikkoman factory one train stop away.

"So why are you drunk?"

I slumped my head back onto my desk. "When have you ever known me to go out drinking in the afternoon?"

She just smiled.

I reached for my pack of smokes and put my feet up on my desk.

It is a distinct smell. Upon exiting the train, passengers are greeted by the pungent, tangy aroma hovering above the platform. It is the Noda City trademark, and a byproduct of the brewing of shoyu (soy sauce), the number one condiment on any sushi counter.

As Japan's first major producer, the Kikkoman Corporation today sells its salty concoction in nearly 100 countries worldwide. Indeed, Kikkoman is clearly the industry Godzilla, and the niche it has carved out in Noda City with its main factory is where it all began.

Finding the source of this heritage is simple: Once exiting the station, follow the fragrance along the main road and beneath a canopy of utility lines until reaching the 12 hulking and rusted steel storage tanks located at the center of the factory grounds.

From the crushing of the wheat and soy to the final pasteurization and bottling, the production process is true craftsmanship. Unlike the average multinational corporation, which cranks out cold-hearted, mass-produced products for the world market, Kikkoman's products are created through methods seen as similar to winemaking in their attention to detail.

From the crushing of the wheat and soy to the final pasteurization and bottling, the production process is true craftsmanship. Unlike the average multinational corporation, which cranks out cold-hearted, mass-produced products for the world market, Kikkoman's products are created through methods seen as similar to winemaking in their attention to detail.

A tour of this factory, which produces a volume to fill one million one-liter bottles each day, is the perfect introduction. A traditional Japanese garden marks the entrance.

Just beyond the entryway is a viewing room from where large circular koji mixing machines can be seen. The visitor is given the opportunity of touching a brown spongy piece of shoyu kasu (fibrous soy).

The main ingredients (wheat and soy beans) mixed in these machines are shipped from the United States. (Kikkoman's main plant is located in a strategic location between the Edo River and Tone River to ensure ease of transportation.)

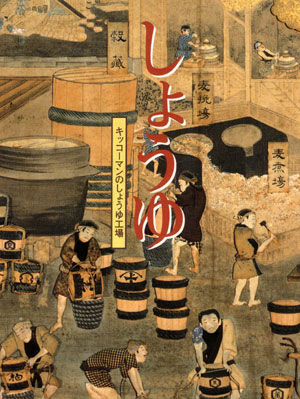

This hasn't always been the case. Shoyu was introduced to Japan from China by a Japanese priest five centuries ago. In the centuries following, as depicted in ukiyo-e woodblock prints, numerous workers, bandana-wearing with pants rolled to the knee, toiled within the Noda plant, hoisting wood barrels upon their shoulders or balancing themselves above the wood tanks while mixing ingredients with long wood sticks.

This hasn't always been the case. Shoyu was introduced to Japan from China by a Japanese priest five centuries ago. In the centuries following, as depicted in ukiyo-e woodblock prints, numerous workers, bandana-wearing with pants rolled to the knee, toiled within the Noda plant, hoisting wood barrels upon their shoulders or balancing themselves above the wood tanks while mixing ingredients with long wood sticks.

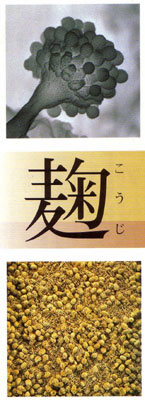

Today, the means of production have moved forward a bit. After the ingredients are crushed, mixed, steamed, and a seed starter added, the standard mash, or koji, is combined with salt and water in large steel containers where it stays for 6 months. Here, proteins become amino acids and starches turn to sugars.

The resulting fermented solution (moromi) is poured over cloths where it is folded and pressed by a machine. The tour takes a break so the visitor can see this process in action.

But perhaps most interesting aspect of the Kikkoman experience is learning of the existence of goyogura, or the Emperor's brew.

The main difference between this special sauce - destined for the Emperor's tempura - and that for the commoners is in the fermentation and subsequent handling. Ingredients are culled from only Japanese farms; wood vats are used to hold the goyogura koji for an entire year; and the filtering process is done by hand. But detailed aspects of this concoction's procedure are kept under wraps to the general public to remain largely as much a mystery as the Colonel's secret recipe.

Both brews are then refined, pasteurized, and bottled. Quality control is of top importance as aji (flavor) and kaori (smell) of the final product are keys no matter the class of the intended user.

Both brews are then refined, pasteurized, and bottled. Quality control is of top importance as aji (flavor) and kaori (smell) of the final product are keys no matter the class of the intended user.

The goyogura variation has a much mightier kick to it than the sauce intended for the great unwashed. Should one wish to sample this firewater - without relying on an invite to a barbecue at the Imperial Palace - it can be had at any supermarket for four times the price of the standard issue.

Kikkoman's production goes well beyond Japan. Over the past 40 years, factories in the United States, Singapore, Taiwan, and the Netherlands (which account for about one-third of overall sales) have opened.

Home, though, is where Kikkoman's heart is, and 317 million gallons of its sauce is consumed in Japan annually.

The tour winds up with an extensive display of all the products manufactured under the Kikkoman brand name. (Other Kikkoman factories in Japan also make wine and canned vegetable products).

Each bottle to exit Kikkoman's factory has a label featuring the company's hexagonal logo with tortoise image inserted in the center. Longevity is the reason for this bit of reptilian imagery. Japanese folklore says that a tortoise can live for 10,000 years. Kikkoman is indeed on its way.

Note: The Noda Shi Station is a one-hour train ride from Tokyo on the Tobu Noda Line.